Having recently attended a three day workshop with Janina Fisher on Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and attachment I thought that I would bring together my reflections on attachment and trauma.

Human babies begin life virtually helpless; their physical bodies and nervous systems are so underdeveloped, they need 24-hour care from their parents or other caregivers. Ideally, during this stage of development, parents not only care for their infant’s physical needs they also care for their emotional needs. They help their child recover from distress, expand their capacity to sustain positive feelings, and teach them how to communicate their physical and emotional needs. This bonding or attachment teaches us that it is safe to be soothed by others and that it is safe to soothe ourselves when loved ones are not available. Studies have shown that the child’s cognitive ability as well as the ability to communicate verbally are dependent upon the quality of parental attachment. Early attachment however is not a single event or even a series of events, it is the result of thousands of physical and emotional experiences: being held, cuddled, fed, stroked, or soothed, and experiencing the loving gaze of our caretakers.

Whether our parents promote a sense of safety, or they frighten us, we do not remember these early experiences of attachment in words or as individual events. In the first three years or so of life, attachment is primarily remembered in the form of nonverbal body memories: emotional, physical, autonomic, tactile, visual, or auditory memories—memories without words. Our attachment or relationship styles are grounded in memories of how we adapted to the relational environment of our childhoods. If we were held lovingly and safely, we feel comfortable hugging others or being hugged by them. If we were held in a frightening or abusive way, our bodies might go tense when people come close to us or pull away even when we are touched in a perfectly safe way. Closeness or physical contact may trigger a surge of fear. Whether we like to cuddle or prefer less physical contact, whether we smile or not, look away from, rather than at people, like being with others or prefer our own company, our relational habits were formed very early in life.

If we feel safety in closeness to our attachment figures when we are very young, we learn to feel safe when they are absent or preoccupied and our capacity to be close to others expands as does the ability to tolerate being alone or out of contact. We may grow up to become adults who prefer more contact or more distance, but we can tolerate less of either when necessary. We learn that relationships are safe, and we learn to how to form healthy interpersonal relationships. In a traumatic environment, there is no safe place. Closeness is rarely safe, but neither is being alone because a child is unprotected when no safe adult is present. Showing emotion is rarely safe either because a child’s sadness or anger often results in abusive and neglectful parents lashing out. Having needs is not safe because normal needs for care and closeness can be exploited or rejected. It is not safe to trust reassurance, and it is certainly not safe to allow abusive parents to comfort us. It is not safe when abusive parents show affection either—nor is it safe to demonstrate loving feelings toward them. Every single aspect of close relationships can become dangerous in a traumatic environment. The child is in an impossible, confusing and distressing situation.

Humans are ‘hard-wired’ to connect, and as infants this connection is to their caregivers, and this is needed for survival. A child’s natural biological response to feeling scared is to seek the attachment figure, to move closer. With abusive or neglectful parents, the problem is that moving closer to a frightening parent is scary, and the body’s other natural response is to move away from something frightening. When the person to whom the traumatised child is drawn towards to find safety is also the danger from which the child is seeking refuge, the child is literally caught between a rock and a hard place. The instinct to cling to the attachment figure when alarmed also triggers the child’s instinct to pull back, but then the pulling back triggers the instinct to move closer, which then increases the instinct to pull back and so on.

As they grow older trauma survivors frequently find relationships, particularly intimate relationships, very difficult to navigate. Sometimes they find themselves fleeing from those who are kindest to them and sometimes they attach to partners who are distant or abusive. They want to get close to a loved one and yet as they become close, they find the relationship frightening and pull away only to want to get close again and so the cycle continues; sometimes this becomes too much for one or the other partner and they end the relationship. Survivors blame themselves for these patterns or tell themselves they don’t deserve to have anyone who shows care and love or perhaps they feel guilty about having someone caring in their life often without really understanding the origin in early traumatic attachment. But the dynamics make perfect sense in a trauma context: a distant or abusive partner triggers the instinct to seek closeness (the scared child part [see next section] will seek attachment for comfort and safety), while the caring, safe partner, who wants to be close, automatically triggers the impulse to flee or fight (the child part has learned that closeness is unsafe). Paradoxically being ‘safe’ in a relationship is ‘unsafe’ and being ‘unsafe’ in a relationship is ‘safe’. All of this can be very confusing and frustrating for both the survivor and their partner.

Trauma and ‘Parts’

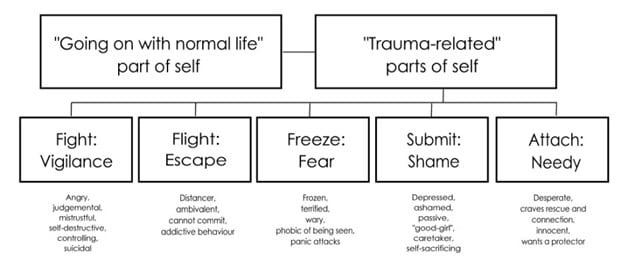

To add another layer of complexity, when children experience trauma their sense of self can divide or fragment (see diagram below). The division results in two main parts: the ‘going on with normal life part’ and the ‘traumatised part’ which consists of many parts. The going on with life part does just that, it tries to live a normal life, it goes to school, to college or university, gets a job, makes friends, often gets married, brings up a family etc.–normal life stuff. It also does it’s best to ensure that nothing from the traumatised part enters its conscious awareness. This is a survival-related division to allow the individual to do two things at once: to carry on as if nothing has happened and to prepare for the next threat—and the next and the next. Both are necessary for survival.

The traumatised part (actually consisting of lots of parts) holds all the trauma memories – these are not coherent, narrative memories in the sense that we can remember what we had for lunch yesterday, they are assorted fragments of images, sounds, smells, body sensations, emotions and sometimes a partial narrative and when these are triggered, they can take over the getting on with normal life part with vehement emotions, impulsive behaviour, intrusive, irrational and compelling thoughts and flashbacks. The emotional brain (limbic system) becomes activated and the more it becomes activated the more the pre-frontal cortex goes ‘off-line’ and we lose our ability to think rationally and logically, to make judgements, to make moral decisions.

These traumatised parts are stuck in trauma-time, they react as 2, 3, 4, 5, 10-year-olds etc., they have no conception that in the real time has moved on, often by decades. In the context of attachment and relationships the survivor often wants to pull away from a loving relationship or will want to continue an abusive relationship whilst at the same time ‘knowing’ that pulling away or continuing is somehow ‘wrong’. They may feel anxiety, fear, depression, anger, guilt, shame, underserving of care or lonely, needy and desperate for care or vacillate between these. It can be very confusing and frustrating to be logical, rational, and functional one minute and then be overwhelmed by emotion and impulse five minutes later. The survivor is at the mercy of an internal world of emotional swings, alarming impulses, and unrecalled actions; without knowing ‘who’ is responsible (or when ‘they’ will turn up).

Remember…

It is important to know that all of this is not done deliberately, it is a survival reaction that goes on largely below the level of conscious awareness. The trauma survivor is not to blame, their mind-body is just doing its best to survive in what is perceived as a threatening situation, it has learned that relationships are generally not safe until proven otherwise. They are not crazy, they are not broken, they are not deliberately being difficult, they just have ‘parts’ that are trying to protect them.

‘They are survivors. If you don’t have respect for their strength, you can’t be of any help. It’s a privilege that they let you in—there’s no reason they should trust you, none. You can’t know their terror. It’s your worst nightmare come true, a nightmare from which you can never awaken. It’s unrelenting. There has been no safety: no one, no time, nothing—all was tainted. Hope was obliterated time and time again. That they are in therapy is in itself a supreme act of valour.’

Anon