I’ve been using polyvagal theory, developed by Stephen Porges, more and more in my clinical work recently. I find it to be a clear and helpful way of thinking about our feeling states that can give us more agency to feel better and to live in a more fulfilling and meaningful way.

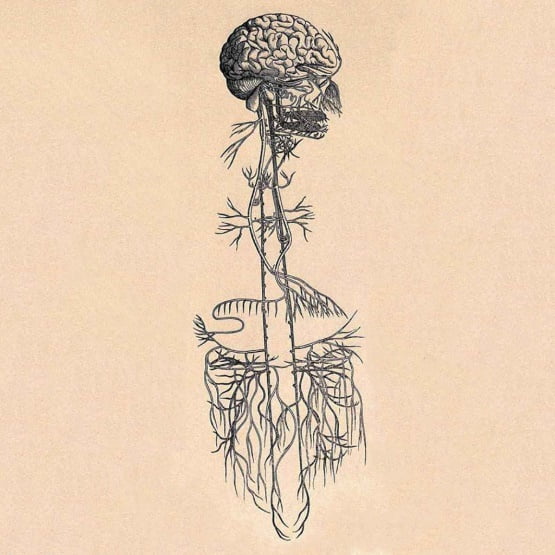

The theory describes the way in which the autonomic nervous system works. Very briefly there are two main nervous systems in the human body: somatic and autonomic. The somatic nervous system operates muscles that are under voluntary control. The autonomic (automatic or visceral) nervous system regulates individual organ function and is involuntary. Opening your mouth is voluntary – you can choose to do it, digesting your food is involuntary – you cannot ‘choose’ to digest food in your gut.

Polyvagal theory:

- explains how the autonomic nervous system (ANS) reacts to experiences and regulates responses

- describes how the ANS takes in information and initiates a response to help us safely navigate ordinary demands made of us in our daily activities including extraordinary challenges that may come our way

- outlines a hierarchy of three biological pathways of response giving us a map of the ways we predictably move in and out of engagement, mobilisation and collapse in response to our experiences

State creates story

Stories about ourselves, the world and relationships are held in our autonomic state. We live a story that originates in our autonomic state, is sent through autonomic pathways from the body to the brain and is then translated by the brain into the beliefs that guide our daily living. The mind narrates what the nervous system knows. Story follows state and because the ANS is shaped over time through the experiences we have, we develop a habitual pattern known as a personal neural profile that then guides our actions and responses.

Our lived experience relies on our autonomic nervous system’s ability to detect safety or threat, a term known as neuroception, and when the autonomic nervous system becomes disrupted, it affects everything about how we move through the world, interact with those around us, and attune to ourselves and the world around us. Neuroception is the word that Porges devised to describe the way our ANS takes in and responds to information both internally and externally. Neuroception is a process that goes on below the level of our conscious awareness.

The Autonomic Ladder

A neuroception of safety brings us into a ventral vagal state, at the top of the “ladder” (see picture below). This is a state of social engagement and connection. From this state you might say the world is a safe place and describe yourself as happy, active and interested. As Porges says, story follows state.

If something happens to alert us to danger (e.g., you are driving and you hear police car sirens, your boss asks for a meeting in a stern tone), we go into a sympathetic nervous system state of mobilisation. This is the state of fight or flight and is evolutionarily linked to mammals. We produce adrenaline, feel anxious or angry and ready for action. The world may feel dangerous, chaotic, unfriendly. You may feel you need to protect yourself.

Going down a step on the ladder, if we sense signs of extreme danger, neurologically we go into the dorsal vagal state of immobilisation. When the danger is ongoing or extreme and we are not able to escape from it, we slip from the state of mobilisation down to the bottom of the ladder. Think of a tortoise drawing its head inside its shell. You might feel frozen, numb, not here, alone, hopeless. From here the world is not safe.

Shifting states

Throughout the day we shift through these states. We work our way up and down the ladder. Some of us live mostly in the ventral vagal zone, but others, often due to adverse life circumstances and trauma, tend to spend more time further down the ladder and have a harder time “climbing” up. If the three states are working in a healthy manner they are all “online” under the overall control of the ventral state which acts as a “brake” on the other two either applying or releasing the brake as necessary. If we have unresolved trauma the states do not work smoothly, there is often little if any ventral braking, instead the states work independently and with little communication between them and as one state gets switched on the other two are switched off.

If we have unresolved trauma in our past, we may live in a version of perpetual fight-or-flight. The sympathetic system in permanently “online”. We may be able to channel this fight-or-flight anxiety into activities such as cleaning the house, working lots of hours or working out at the gym, but these activities will have a different feel than they would if they were done with the ventral vagal system “online”.

For some trauma survivors, no activity successfully channels their fight-or-flight sensations and as a result, they feel trapped and their bodies shut down. These clients may live in a version of perpetual shutdown, depression and hopelessness. The more time we spend on different points on the ladder, the more we’re likely to get stuck in negative patterns. Porges even suggests we develop related physical symptoms including irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia.

Polyvagal-informed therapy offers tools to help you be closer to the top of the ladder, more of the time. In Deb Dana’s book, The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy which informs this article, there many tools for mapping out your own nervous system ladder, including how you can help yourself climb up the ladder.

How can this theory help you?

Understanding your nervous system in this way can change the way you think of these states in yourself. Therefore there can be less self-judgement and more compassion for your state.

By recognising what state you are in a given moment, and understanding how you shift between states, you can learn to change your state so you can feel connected and safer more of the time. You can feel less hopeless when you’re in the dorsal vagal shut down state, as you’ll know ways to help yourself out of it. You can also more easily enlist the help of others in this, since as humans we need connection with others to feel safe.

This theory, as I mentioned above, is especially relevant for those with trauma in their background. A trauma history often creates a hyper- or hypo-vigilant state, where either one is scanning for safety all of the time, and one can interpret neutral events or interactions as threatening ones, or one is shut down and depressed. This is a natural result of trauma as our nervous systems have had to protect us against danger and have now got used to that protection mode, your mind and body did what was required to help you to survive. The good news is that through positive connections (and possibly some therapy) we can help retrain the nervous system to be able to relax and feel safe.

Much of the trauma work I specialise in helps regulate nervous system states to bring you “up the ladder”.

The polyvagal ladder, adapted by Deb Dana. Source: NICABM.